by Luca Fiore

The welcome republication of her debut book, On The Sixth Day, offers an opportunity to retrace, in perspective, the work of one of the great names in contemporary photography: Alessandra Sanguinetti. The volume, which first appeared in 2005 and soon went out of print, greatly contributed to the success of the Argentine photographer, born in New York and raised in Buenos Aires, who is now a prominent member of the Magnum Photos agency. From this first and important work stem the two subsequent projects that earned her true notoriety: The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Enigmatic Meaning of Their Dreams and The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer. All three books, published by the British publisher MACK, were made in the Argentine countryside, on a farm near the one where the photographer spent her summer holidays for twenty-five years. Guille and Belinda are two cousins, granddaughters of Juana, the keeper of the animals to whom On The Sixth Day is dedicated.

The book, square in format like the images it contains, has on the cover a photo of two white lambs tied together by a thin rope around their necks. The one on the left has its head covered by a hood and veers toward the edge of the photo. The other is being tugged by its companion and seems to be trying to break free. The two pale figures emerge from a completely out-of-focus background. Their heads and limbs are in motion; only the woolen fleece is clearly visible in detail. The horizon divides the yellow-green plain from the gray-purple sky. The lens frames the two animals tightly. The point of view is at the animals’ eye level. This is the key stylistic choice that supports the entire book, which is, in Sanguinetti’s intention, a tribute to the domestic and wild creatures that enliven rural life on the vast Argentine plain. The dedication, at the end of the long sequence of images, reads: “This book is dedicated to the extraordinary lives of farm animals everywhere. For all they go through, all they give us and all we take from them.”

“I wanted to show a reality that is rarely told,” Sanguinetti explains to Domani: “And it is never told by looking at the true protagonists, which are the animals themselves. Mine is a tribute, but I wanted to make it without concessions, without sentimentality or idealization. No matter how well you know an animal, you will never be able to truly understand it. It’s already hard enough with a human being. My partner, the person I know best, remains a mystery. Let alone an animal.”

It is a book without compromise. The colors are as vibrant as those saturated by the exuberant light of the Argentine sun. The green-green of the grass, the brown-brown of the earth, the blue-blue of the sky. And above all, the red-red of blood. There is a lot of it throughout the sequence. The blood of animals killed, skinned, even aborted. “It is the normal life of farms, where every day the farmer kills an animal to feed his family. There is no intention to condemn, no finger-pointing. If I had wanted to denounce violence against animals, I would have gone to photograph somewhere else: in factory farms.”

As mentioned, the framing is almost always at the animal’s eye level. There are portraits of the horse and the hen. Of the cow and the chick. The duck and the rabbit. A group of dogs barks, who knows why, at a disoriented pig. It is a choice that forces the viewer into an incredibly close gaze, dramatically reducing the distance from the subject. But this closeness, due to technical reasons, also produces a notable reduction in depth of field, leaving only the subject—or even just part of it—in focus, enhancing the sense of intimacy. Many of these shots have all the characteristics of classical portraiture, with the sole difference that the subjects are not human beings. “I don’t believe that showing an animal’s character means humanizing it. Even because, even in portraits of people, you end up projecting onto the subject something that might have nothing to do with that person. My animals are neither metaphors nor symbols. They are what they are.”

And yet, even though it is first and foremost a documentary work, it is impossible not to perceive in the succession of these photographs a poetic impulse that touches on ultimate things: life, death, joy, suffering, the sense of fate. In itself, the style in which they are made would suffice to render them verses of a poem about the intertwining of tenderness and violence that takes place on an Argentine farm. But to this is added the biblical connotation given by the title of the work, which refers to the sixth day of creation, when God created animals and man, and gave the latter dominion over all other creatures. A choice that seems to lift the images out of a historical and specific dimension and elevate them to a mythical and universal one.

At the same time as On The Sixth Day, Sanguinetti explains, the work with Guille and Belinda began—two cousins roaming around the farm while the artist was focused on animal portraits. From time to time, the two girls—nine years old at the beginning—enter the frames, appearing in the background of the animals’ life. Then, gradually, the photographer begins to observe and interact with them, in a dialogue that becomes first complicity, then friendship. The first book dedicated to them has a rather descriptive title: The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Enigmatic Meaning of Their Dreams. The girls are first photographed in everyday rural gestures, then in dress-up games that become a series of mise-en-scènes of nativity scenes, angelic images, jealousy dramas, jokes about future motherhood. In one shot, Guille and Belinda appear emerging from the waters of a stream like a pair of Ophelias in brightly colored clothes. At times these are dream-dreams or sacred representations, while at others they appear as prophetic visions.

“As the two girls grew up, I had to change my approach to them,” Sanguinetti explains today: “At the beginning it was easy to play together, but then they experienced a sudden transition from childhood to adulthood, since Belinda married at sixteen and became a mother at seventeen.” This phase of transition is the theme of the next book, The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer. The two young women are no longer innocent souls dancing in open fields, but appear inside a modest room, cooking, cleaning, and studying. Carefreeness and play are replaced by a more everyday poetry, where mischief gives way to hidden kisses, and the fake baby bumps made with pillows become real. Heartbreaking sunsets appear, dusks of a day that is the season of a life. “It’s been twenty-five years now that I’ve been seeing them, and every time I go back I just want to visit and spend time with them, like with friends, without the camera somehow coming between us again,” she recounts. “And yet, every time, I can’t help it—I always end up bringing home a few shots.”

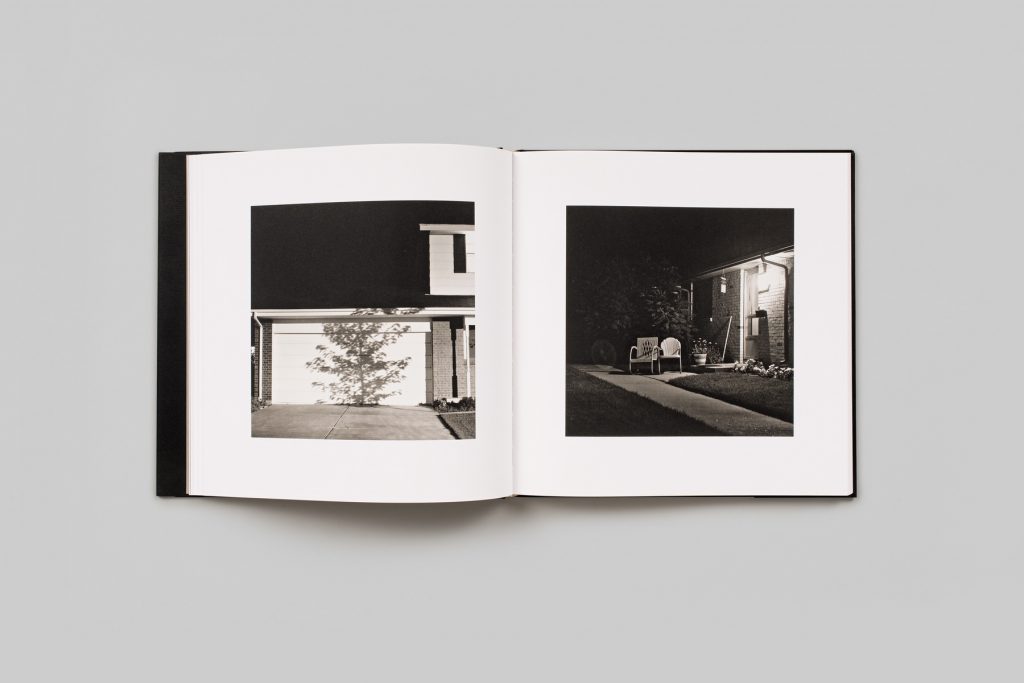

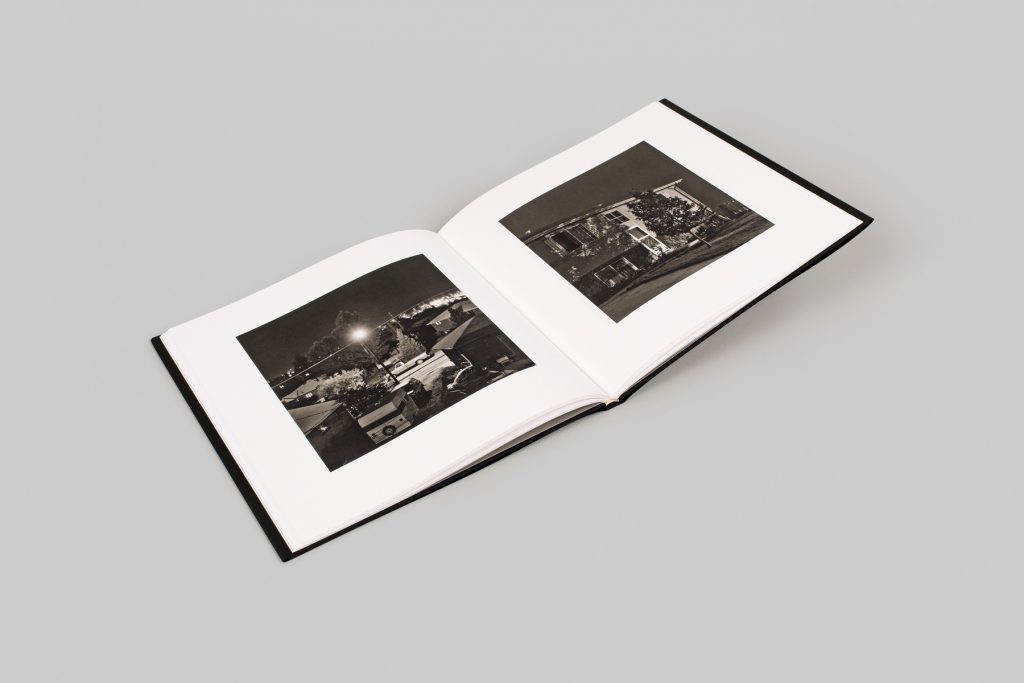

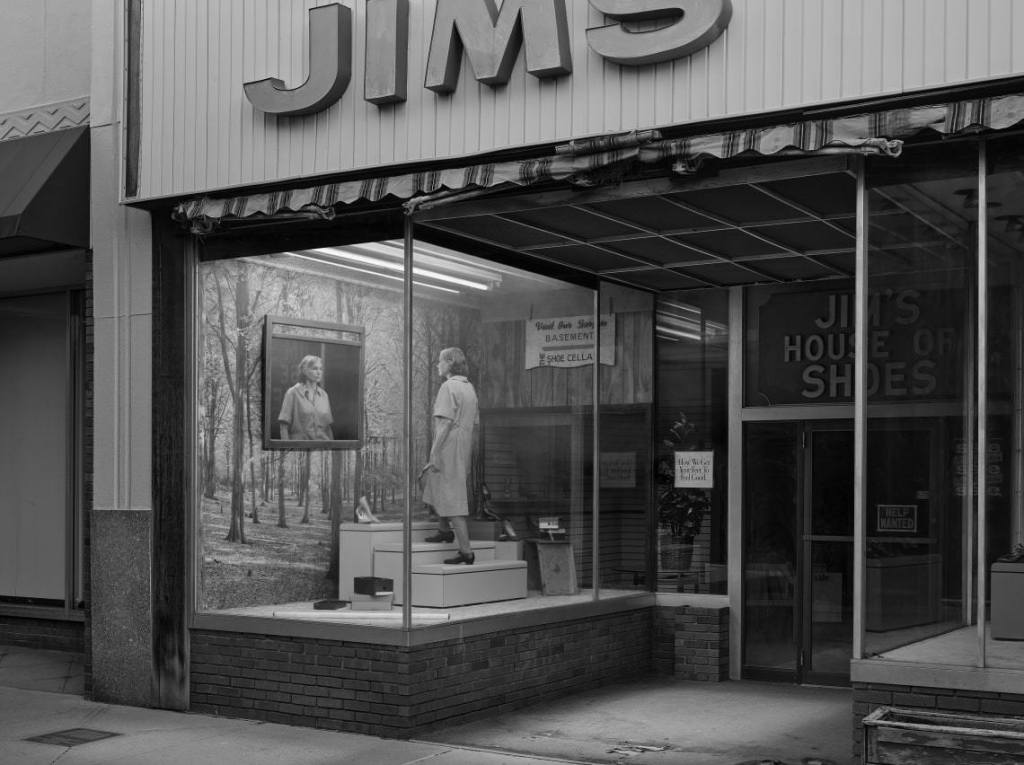

In her latest work, Some Say Ice (MACK, 2022), Alessandra Sanguinetti returns to the same themes—animals and children—but in a completely different context and with a style almost opposite to what we had come to expect from her. It is a collection of images in refined black and white, taken since 2014 in the small town of Black River Falls, Wisconsin. This is the same place featured in Wisconsin Death Trip, a book of photographs taken by Charles Van Schaick at the end of the nineteenth century, documenting the life and death of its inhabitants. Sanguinetti found a copy of that volume on the shelves of her home in Buenos Aires when she was still a child. Contemplating that series of faces—often photographed post-mortem—was the moment, the artist explains, when she first recognized the reality of her own mortality. In Some Say Ice, animals are depicted like sculptures. The faces of children, young people, and the elderly are austere. Icy. Winter dominates the landscape. The title of the book is a line borrowed from a Robert Frost poem: “Some say the world will end in fire, / Some say in ice.” “While I was working in Black River Falls, it felt like I was trying to solve a mystery or find the culprit of a crime,” Sanguinetti explains. “I was looking for clues to find a valid answer to something for which there can be no valid answers.” It was, the artist continues, a kind of exorcism to ward off the fear of death. It is likely here that the threads first woven in the Argentine countryside are tied together again—where the white fleece of the lambs was stained with red blood, and the dream of childhood faded into the arid truth of everyday life: “The reason I photograph—and perhaps the reason all of us do, whether we admit it or not—is that we don’t want to disappear. Every image, even the most banal selfie, is a kind of denial of death.”