by Luca Fiore

His photography has been compared to the painting of Edward Hopper, the cinema of David Lynch and the prose of Raymond Carver. A mixture of a sense of isolation, restlessness and hyperrealist surrealism. Film stars such as Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Gwyneth Paltrow and Tilda Swinton have appeared in his images, constructed in every detail by a crew of dozens. Gregory Crewdson, born in Brooklyn sixty years ago, is one of the most acclaimed photographers of the moment: teaches at Yale University in the Master of Photography program and exhibit at Gagosian in New York and White Cube in London. These days, at the Turin branch of Gallerie d’Italia, he is presenting three series of works conceived between 2012 and 2022: “Cathedral of the Pines”, “An Eclipse of Moths” and “Eveningside”, the latter commissioned for the occasion by Intesa San Paolo and which gives the exhibition its title, and “Fireflies”, a cycle from 1996. It is a trilogy in which Crewdson’s style is exercised by being faithful to his interest in Middle Class… and vernacular American settings, but abandoning the surrealistic and grotesque excesses of the early days and concentrating on the places of a particular region: that of the rural towns of Massachusetts, where his childhood holiday cottage was located, where his companion was born and where he found a home in 2012 in a former Methodist church.

But in order to understand Crewdson’s complex world – in which references to painting, film and literature merge – we probably need to go back to Brooklyn, where his psychoanalyst father used to receive patients in the basement of his house, just below the living room. The photographer recounts that he would see people coming from the street and entering his father’s office, whereupon he would lie with his ear to the floor in an attempt to pick up the confidential dialogues. He recounted this in a dialogue with Cate Blanchett, saying: ‘I never really succeeded, but that gesture I think was decisive for me, it was trying to look into everyday life and look beneath the surface for a secret, something forbidden and trying to project an image in my head of what it could be’.

His first encounter with photography was at the MoMA where, at the age of ten, he visited the Diane Arbus retrospective. At sixteen, he was the frontman of the Speedies, a pop band whose first single was entitled “Let Me Take Your Photo”, later used for a Hewlett Packard advertisement. He studied photography in New York with Jan Groover and Laurie Simmons, two leading figures in the American scene of the 1960s and 1970s, and then specialised at Yale. His thesis work is a series of portraits of the residents of Lee, Massachusetts, where his parents took him on summer holidays.

The first series of images that attracted the attention of critics was ‘Twilight’, shot between 1998 and 2002, where he consolidated what was to become his trademark: large-format photographs with a realistic feel but staged with the help of a film crew, which helped him create sets, costumes and lighting effects. Saturated colours, extensive but skilful use of digital retouching. Indoor and outdoor situations are portrayed, with one or two characters, usually in a night-time setting, recalling atmospheres from the film ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’: beams of light raining down from above, trees growing in the living room smashing through the floor, women floating on a mirror in the middle of the living room, a giant beanstalk rising to the sky in the backyard, a myriad of colourful butterflies emerging from the shed in the garden. The protagonists watch in dismay or impassively. Enigma mingles with disquiet; a sense of threat coexists with surprise.

In the next series, ‘Beneath the Roses’ (2002-2008), Crewdson continues to construct images using the cinematographic method, but the situations become more intimate, less bizarre but full of narrative tension. Less Steven Spielberg, more Alfred Hitchcock: a pregnant woman stopped at a pedestrian zebra crossing at dawn, the only human presence in a deserted street; a man in a night rain in the middle of the street, while his car is pulled up to the curb with the door open and an abandoned briefcase not far away; a couple in the bedroom, he in his pyjamas sitting on the mattress, she standing in her underwear, her back to him.

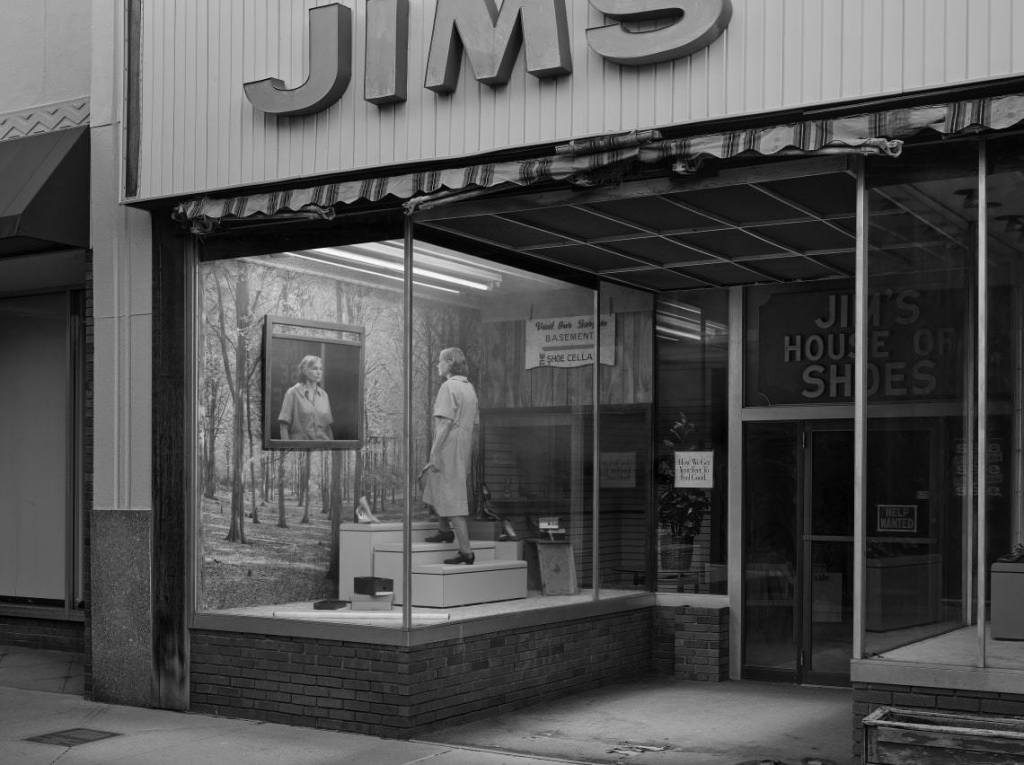

Crewdson’s style seems to evolve by small degrees. More than the technique, it is the theme addressed that makes the difference. ‘Cathedral of the Pines’, for example, is a reflection on the idea of shelter. What takes place here is the presence of the natural landscape: the forest, the river, the snow. ‘An Eclipse of Moths’ is made in Pittsfield, the place where Herman Melville wrote part of ‘Moby Dick’. Here, it reflects on contemporary America and its relationship with its history and cultural heritage. For years, the inhabitants of the town were almost all employees of General Electrics. Due to a scandal involving the use of a toxic substance, the plant was forced to close and Pittsfield slowly depopulated. The images of ‘Eveningside’, on the other hand, are in black and white, recalling the atmosphere of the film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s. It is a portrait, even more accomplished than the previous works, of an atomised and psychologically paralysed society, at an emotional standstill, where the drama is all within. Like a bomb ready to explode.

But beyond the themes dealt with, Crewdson’s work forces us to reflect on the photographic medium as such. It is true: since its invention, photography has been forcing us to think about its status. Over the years, and the evolution of technologies, the questions, instead of thinning out, have become more frequent. The first theme is that of ‘mise-en-scène’. The American artist, in this sense, is part of a tradition linked to artists such as Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman, who since the 1970s have started to use photography no longer to record real-life scenes, but to represent invented situations. More in Wall’s wake than Sherman’s, Crewdson intends to stage instants of narratives that find their fascination in enigmatic fixity. What is striking about his work is the particular quality of realism. If one of the achievements of modernist photography had been to create works of art that did not attempt to emulate the results of painting, but took the medium’s own characteristics to the highest level (‘My intention is to make photographs that look more and more like photographs’, said Alfred Stieglitz), Crewdson returns to a kind of pictorialism, not only because he ‘invents’ what he represents, but also because – paradoxically – his images end up looking more like a hyperrealist painting than a photograph. The first characteristic of this ‘hyperrealist surrealism’ is the crowding of details that the artist disseminates in the image. They are clues to hypotheses for reading the image. Quotations (the street names) or winks (the car number plates bearing his initials) completely absent in a painter like Hopper, to whom Crewdson has often been compared. The other is the ‘all in focus’ which, in the confined space of a room, is technically impossible to achieve with the tools of photography and is the result of careful digital post-production. What we see is more like the way we see with our eyes (which is the result of an optical illusion produced by our brain) than the much more rudimentary way we see with the more sophisticated cameras. Another aspect that distances this type of image from photographic vision – and this time from that of our eyes – is the use of artificial lighting in scenes of natural light. Crewdson’s works are the result of combining many shots and the protagonists are portrayed separately, lighting them with cinematic spotlights. As a result, the light is often inconsistent with the context. The mastery of post-production is to ensure that the unnatural effect is at least plausible at first glance and not immediately recognisable. If one often hears people say of a painting “it looks like a photograph” and of a photograph “it looks like a painting”, here we are faced with a photograph that looks like a photograph, but it is a photograph in a very different sense from that intended by Stieglitz.

Another major theme posed by Crewdson’s work is the narrative capacity of photography. There are several names of literary greats to whom his images have been juxtaposed: Raymond Carver, John Cheever, Joyce Carol Oates, Alice Munro and others. It is curious that single shots, which capture an instant, are able to render the feeling of a ‘story’, i.e., a narrative unfolding over time. Garry Winogrand said: “Photographs are silent, they have no narrative capacity. You know what something looks like, but you don’t know what is happening. You don’t know whether the hat that is being held is about to be put on your head or has just been taken off’. This is, paradoxically, also what Crewdson thinks, who said in an interview: ‘Despite all the talk about my photographs being narratives or about storytelling, very little actually happens in images. A photograph is frozen and mute, there is no before and after. I don’t want there to be a perception of any kind of literal narrative. That is why I try not to give weight to motivation, plot or anything like that. I want to privilege the moment. In this way, the viewer is more inclined to project his own narrative onto the image’. The story, one might say, is in the eye of the beholder — in the innate need for narration. In other words, in the fact that facts must somehow have a direction, a sense. Yet there is, beyond a certain setting in provincial America, and the feeling of paralysis, another kind of relationship with literature that, especially in the 20th century, has become less ‘narrative’ than in the previous century. A writer such as Carver, for instance, as well as someone like Flannery O’Connor, does not rely on the ‘plot’ or the ‘fabula’. Often the stories are truncated without the protagonists’ story being brought to completion, almost as in a Crewdson photograph. And, perhaps, the reasoning should be reversed to think that it is literature that finds its strength when it is able to produce images. Perhaps it is useless to bother with T.S. Eliot’s ‘objective correlative’, we need only recall the episode in “Cathedral” in which Carver “photographs” the blind man who asks his guest to describe to him what a medieval church looks like and, faced with his inability to do so, the two of them grasp a pen and the sighted man guides the other’s hand in drawing on the paper. An unforgettable image, regardless of what happens before and after in the story.

There is one last aspect worth considering. Despite Crewdson’s desperate image of the human situation, the artist does not consider himself a pessimist. “These images were made in the middle of summer, a crucial time,” the artist explained in his dialogue with Cate Blanchett, referring to “An Eclipse of Moths”: “The relationship between these industrial landscapes and the looming nature gives a certain feeling of underlying anxiety. But in the end, it’s about renewal, and I think that’s really key: nature persists. I think in the end the photographs offer a sense of hope, or beauty, or even redemption”. In this series of works, much more than in the others, in fact, if one does not consider the human figures and their situation of material or spiritual misery, the vegetation and atmospheric skies of dawn or dusk convey an unequivocal sense of peace. It is no coincidence that the photographer uses the word ‘redemption’, as the first photograph in the series shows a building with the very inscription: ‘Redemption Centre’. Yet there is also another aspect to be considered. “If my pictures have a meaning, I think it is to try to make a connection with the world,” he explained: “In a way, I see them as more optimistic. Even though there’s clearly a level of sadness and disconnection, I think it’s about trying to make a connection and the near impossibility of doing that. And I think maybe the figures in my work are stand-ins for my need to create a connection”. It is therefore a kind of negative philosophy, which denies in order to affirm. The representation of a frustration, to accentuate the presence of the desire for an absent good.

It is no coincidence that the curator of the Turin exhibition, Jean-Charles Vergne, also decided to include the ‘Fireflies’ cycle, a series of black and white photographs of fireflies, which Crewdson took in small and medium format analogue. In some cases, they are visions of fields at dusk where the small lights can be seen, in other images the fireflies are trapped in a mosquito net or a jar. It is hard not to think of the long-distance controversy between Pier Paolo Pasolini and George Didi-Huberman over the ‘disappearance of fireflies’. If for the Italian intellectual it is a metaphor for the cultural genocide practised by the new fascism of the consumer society, for the French philosopher not only have the little lights not disappeared, but their presence is the glimmer of a positivity that resists despite everything. In Crewdson’s fireflies, one can see the plastic image of Didi-Huberman’s positive realism, which opens a glimmer of hope.