In a dazzling 1998 New Yorker article, the great Peter Schjeldahl wrote: “Nan Goldin is two people—a needy sentimentalist and an adamantine aesthete, who unite to make her one of the best art photographers of the last twenty years. If you’ve lived much, you know both types. The emotionally blundering sentimentalist dewily loves humanity in general while falling in miserable love with a monotonous succession of human beings in particular, each somehow exactly wrong. The aesthete, one almost believes, would heave his or her own grandmother out of a speeding car if it promised a glimpse of perfection.” One must envy Schjeldahl’s critical lucidity more than his empathy. Indeed, he continues: “Sentimentalists and aesthetes are born to loathe each other. The sentimentalist recoils from the aesthete’s visions of orderly bliss, which purportedly serve the human heart while coldly using it, and maybe even using it up. The aesthete would like the sentimentalist to dine on broken glass for the sin of presuming to nurture ‘creativity.’ The two temperaments are fire and ice.”

“This Will Not End Well,” at Pirelli Hangar Bicocca in Milan (open through February 15), is the perfect occasion to verify how right Schjeldahl was. Beyond being the most complete retrospective of the artist born in Washington in 1953, it’s a unique opportunity to experience her work in its original format: the slideshow. Books, catalogs, photographs elegantly hung in white cubes could never replicate the experience of sitting in a dark room watching wall-sized projected images accompanied by a soundtrack usually composed of extremely famous songs. The Milan exhibition, previously shown at Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2022, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2023, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 2024, and heading to the Grand Palais in Paris next year, presents eight projections ranging from 15 to 42 minutes in length—nearly three and a half hours in total. If the subject matter of Goldin’s entire oeuvre didn’t advise against it, one might say there’s a risk of overdose. But it’s a risk worth taking with proper precautions: admission is free and you can return multiple times.

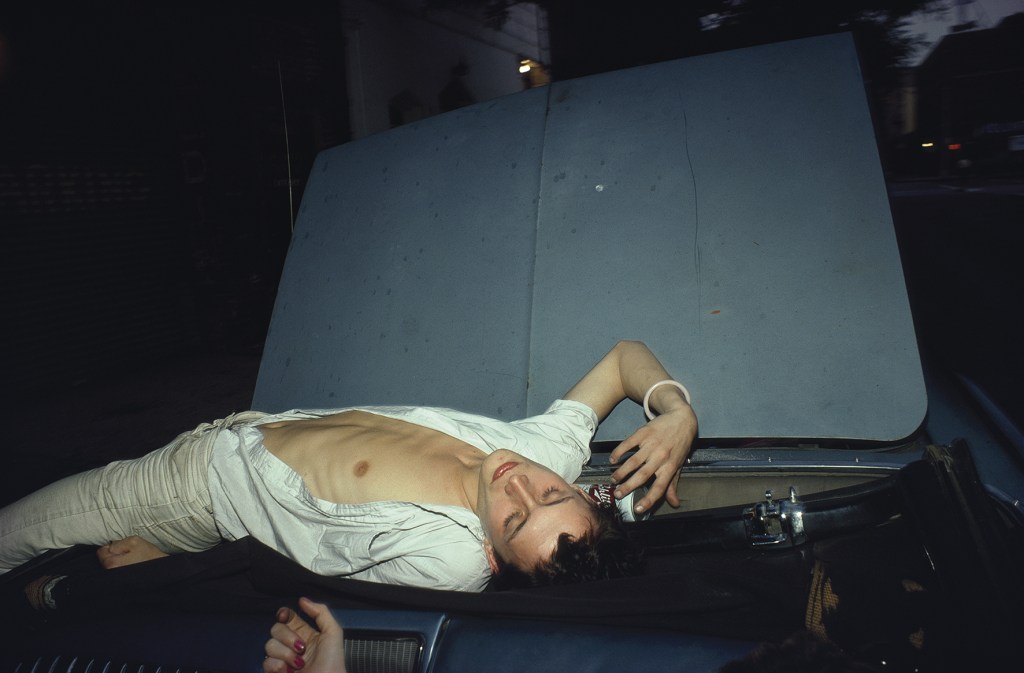

Nan Goldin’s fame is inextricably linked to “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency”: roughly seven hundred portraits of people from her closest circle during her bohemian life between the seventies and eighties. Boston, Provincetown, Berlin, London, but above all New York’s Bowery. Friends, lovers, stars of the underground scene—all are photographed with raw tenderness. Parties, moments of relaxation, intimacy inside and outside almost always squalid bedrooms. Kisses, embraces, sex, and bruises too. Physicality displayed in all its forms, including the ambiguous and exuberant world of drag queens, portrayed fearlessly in the years immediately following the Stonewall riots. The slides, with their saturated, dense colors, succeed one another rapid-fire, without allowing the eye to linger on details. One slap after another. The musical element is not background but a soundtrack that interacts—here dramatically, there ironically—with the flow of images: “I’ll Be Your Mirror” by the Velvet Underground, “She Hits Back” by Yoko Ono, “Sweetblood Call” by Louisiana Red. The reference to music is actually already contained in the title, borrowed from an aria in Bertolt Brecht’s “The Threepenny Opera,” placed right at the beginning of the playlist.

The slideshow was the method Goldin chose from the start, making virtue of necessity—slides cost less—to show her work in Manhattan clubs, where initially the audience coincided with those portrayed. With each screening, the sequence changed and expanded, as did the music. The “ballad” first left the underground circuit when shown at the Whitney Biennial in 1985 and then published the following year in book form by Aperture. The soundtrack assumed its current composition in 1987, but the slide sequence, conceived as a visual diary, continued to evolve. Over time, however, the story of life “on the wild side,” as Lou Reed would sing, had to reckon with the mounting deaths from the HIV epidemic. Those same beauties, both pure and damned, portrayed just a few years earlier, now became expressionless faces in coffins. Thus the “Ballad,” in its definitive version, concludes with a photograph of graffiti showing two skeletons embracing—Eros and Thanatos—becoming a long elegy for lost friends and lovers. Thirty are named in the closing credits.

It would be a mistake, however, to think the value of this epic and lyrical work lies solely in “storytelling.” Nan Goldin’s artistic roots run deep into certain masters of American photography. As Schjeldahl writes again: “Evans, Frank, and Arbus were progressively more explicit photographer-laureates of the abyssal lack—the wanting, the want—that defines American soulfulness. Think of the largest genre of our nation’s artistic symbols: melancholias of city, suburb, town, and farm; the solitude (not loneliness) of Edward Hopper; the choiring voids of Jackson Pollock; emptinesses of open roads, prairies, rivers, and ocean; the ache of the blues; the light across the water from East Egg; the whiteness of the Whale.” But in this list of patron saints of American art, the New Yorker critic forgets to include a certainly lesser name, but one without which Goldin’s direction cannot be understood: Larry Clark, photographer and filmmaker born in 1943 who published a scandalous photobook titled “Tulsa” in 1971. The author explains: “I was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1943. When I was sixteen I started shooting amphetamine. I shot with my friends every day for three years and then left town, but I’ve gone back through the years. Once the needle goes in, it never comes out.” The book is a collection of images Clark made during those years when beauty and damnation mixed in an elixir as intoxicating as it was toxic. Unlike Evans, Frank, and Arbus, who observe the abyss from above, Clark and Goldin show it to us as they plunge into it.

This artistic genealogy helps better understand the thread running through “This Will Not End Well.” The impression one has at the end of viewing the eight projections is that “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” is not so much the artist’s first and most successful work, but rather the beginning of a never-concluded project that produced, by germination, all her other works. Not only because we see how much the artist draws from the Ballad’s corpus to nourish the other sequences, but because each slideshow is nothing other than the in-depth development of one of the many themes already present in that guiding sequence. Take “The Other Side” (1992-2021), a homage to the transgender friends Goldin lived with in the early seventies and whom she first began to portray, who naturally also appear prominently in the Ballad. The same goes for “Fire Leap” (2010-2022), a tender parade of children featuring the artist’s godchildren and friends’ sons and daughters. Pregnant women (nude, of course), births, nursing, games, gazes scrolling across the screen accompanied by a children’s choir singing David Bowie’s “Space Oddity.” Flashes of innocence in the whirlwind of a life as beautiful as it is damned.

The HIV epidemic isn’t the only one Goldin has survived. There was also the opioid crisis, into whose trap she personally fell. This story, along with her parallel career as an activist first for AIDS patients’ rights and then in the campaign against art institutions’ acceptance of funding from the Sackler family, responsible for spreading the infamous OxyContin, is well told in “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” Laura Poitras’s film, which won the Golden Lion at Venice in 2022 and was nominated for an Oscar the following year. “Memory Lost” (2019-2021) is an attempt to render in images the hallucinatory experience of substance addiction. The photographs are systematically out of focus. The claustrophobia of interiors alternates with blazing dawns and sunsets. Telephone dialogues are heard. Skewed music. The political activism that has marked Goldin’s career today also finds expression in support for the Palestinian cause, explicitly referenced at the end of each projection.

“You Never Did Anything Wrong” (2024) is instead a film, shot in Super 8 and 16mm, dedicated to animals. The title comes from an epitaph for a pet that the artist found and filmed in Portugal. It’s Goldin’s most abstract and lyrical work, in which she steps outside her usual playing field: autobiography. “Stendhal Syndrome” (2024) is the evolution of work begun at the Louvre, where she started juxtaposing photographs of artworks with those from her own archive depicting relatives and friends. Simultaneously, Goldin shows the sometimes truly uncanny resemblance between art and life and retells, in her own way, stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Pygmalion, Cupid, Narcissus, Diana, Hermaphroditus, and Orpheus. Part classical culture and art history refresher, part memento of the reciprocal relationship between art and life.

The exhibition concludes in the large “cube” space at Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, over 20 meters high, which the American artist uses to house “Sisters, Saints, Sibyls” (2002-2022), a three-channel video installation that is an ode to her older sister Barbara, who died by suicide at 18. Barbara is also the person to whom “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” was dedicated back in the eighties. Goldin returns, once again, in an infinite spiral around the indissoluble knot that has gripped her soul her entire life and that has always generated the creative and self-destructive energy displayed in this major exhibition. It’s an indictment of parental responsibility, without the verdict being pronounced, but left to hover in the space with its reinforced concrete walls. In the center of this space is displayed a sculpture representing the artist lying in her bed, immersed in a dream or waking nightmare. The editing is calculated and effective, and the 35 minutes of visual and verbal narrative flow smoothly, though painfully. Occasionally, Goldin seeks emotional impact by turning to Johnny Cash, whose voice accompanies images of self-harm: “I hurt myself today / To see if I still feel. / I focus on the pain / The only thing that’s real.”

In the finale of “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” an interview Goldin conducted with her parents before they died is shown. At one point, the mother mentions a note found among Barbara’s belongings, the suicidal daughter, which contained a passage, typed out, from Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”: “Droll thing life is—that mysterious arrangement of merciless logic for a futile purpose. The most you can hope for is some knowledge of yourself—that comes too late—a crop of unextinguishable regrets.” And there, also in light of the Milan exhibition, comes the suspicion that this note contains not only Barbara’s testament but the entire poetics of her sister Nan. Regret belongs to survivors, and Goldin is a survivor of two perfect storms: AIDS and OxyContin. If we had to say what kept her alive, beyond the mysterious energies of the universe, one would say: that small crowd of faces and affections she surrounded herself with and never stopped portraying. As if art, together with the capacity to attain self-knowledge, had the power to affirm an illogical positivity of life (“Images in spite of all,” as Georges Didi-Huberman would say). Life which, in its elusive entirety, is the incandescent core that ignites all of Nan Goldin’s work. This is perhaps why it conquers us even in its harshness. Yet there hovers, impossible to ignore, that title steeped in black humor: “This Will Not End Well.”

Il Foglio, December 13-14, 2025