by Luca Fiore

One day in the mid-2000s, Batia Suter received an email from someone asking about the relationship between her work and Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. The sender had seen a draft of what would later become Parallel Encyclopedia, her first book, published in 2007 and now considered legendary. In her Amsterdam studio, the Swiss artist had to Google the name of the great German scholar—she had no idea who he was. It took only a few seconds for her to realise the near-overlap between their projects. Today, she tells Il Foglio it was a shock that took her two weeks to recover from. “What was the point of continuing such an immense effort if someone had done the same thing a century earlier?” She ordered books, read, studied. What unfolded before her was the fascinating and mysterious world of the German art historian and critic—“Hamburg at heart, Jewish by blood, Florentine in soul”—who, during his lifetime, amassed a collection of 65,000 books and 8,000 photographs of artworks. In the last years of his life, he began working on an unfinished project: panels grouping images of artworks from all eras to show how certain iconographic themes in Western culture repeat over time. A utopian and marvellous undertaking. A new way of studying art history through photographic reproductions. An adventure abruptly cut short in 1929 by a heart attack.

Instead of being paralysed by the comparison, Batia found in Warburg a companion along the way. “I had found someone who was familiar with my way of thinking. I began to feel him as a brother, in who he was and in the way he researched. Back then, he had to order images from all over the world, spending a lot of money. I, on the other hand, had the privilege of simply scanning them from the books I collected. Of course, he was interested in Greek culture, the Renaissance, the workings of the human body. I’m not very good at building theories. Mine is more an attempt to make high culture and low culture collide.” Indeed, Parallel Encyclopedia—a 600-page volume created over five years of intense, obsessive work—is less a tool for study and analysis than an epic of the gaze. Monumental in its encyclopaedic scope, it seems to play with, if not poke fun at, the rationalism of Diderot and company. Yet it contains an immense love for the power of images: their ability to speak their own language and to converse with one another, generating unexpected new meanings.

Nearly twenty years after the publication of Parallel Encyclopedia, Batia Suter is a prominent name in the world of photography. Few, like her, have worked so convincingly and radically with archival research—a field that has become one of the most beloved and developed strands in contemporary photography. Alongside her publications, Suter has translated her research into monumental installations using her image collections. She was a finalist for the prestigious Deutsche Börse Photography Prize in 2018; that same year, she exhibited at Le Bal in Paris, one of the most important photography venues. This year, she won the Swiss Design Award and is present with a solo exhibition at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, titled Octahydra. In the current display of the Stedelijk Museum’s permanent collection in Amsterdam, her installation drawn from Parallel Encyclopedia is on view—80 books, open and overlapping, so that their photographs engage in visual dialogue.

Suter’s passion for images began early, at the age of 14. That’s when she started carrying a camera with her everywhere. She would spend hours developing and printing film rolls in the darkroom. She enrolled at the School of Design in Zurich, then transferred to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Arnhem, the Netherlands. “I began painting and drawing by enlarging my photographs. I would project the images and trace them—a very physical and intense process. But it was also stressful—I had to work at night to have the darkness needed for projection, and I needed large spaces. I realised I couldn’t go on like that until I was eighty. Even then, I wasn’t interested so much in the technique—whether painting or photography—as in understanding images and their effect on me.” After the academy, she enrolled in a master’s program in typography. It was the late 1990s, and Batia had no experience with computers, but in that course she discovered two programs that would irreversibly shape her career: Photoshop and QuarkXPress. The first for working on scanned images, the second for laying them out on the pages of a potential book. “That’s when I started collecting second-hand books. I began scanning all the images that interested me. I would print them on A4 sheets and lay them out on the floor. I worked in an open space, and lots of people would pass by. At a certain point, they started stopping and asking for copies of the images that had caught their attention.”

That’s when Batia realised something fundamental: her thinking moved through images. Not only that—everyone has their own favourites depending on their past and interests. Yet there are some images that appeal to everyone. “There are photographs that relate to something we have in common. There’s something in them with a particular power, able to captivate us.” This became the starting point for her research. What are these images? Why are some timeless? She wanted to understand. Her passion for images became like a drug—a kind of addiction. And when she began working with page-layout software, she felt a new sense of freedom. The ability to experiment—more easily than ever before—by juxtaposing, swapping, and inverting her collected material opened a frontier of exploration that seemed endless. She had finally found her tool.

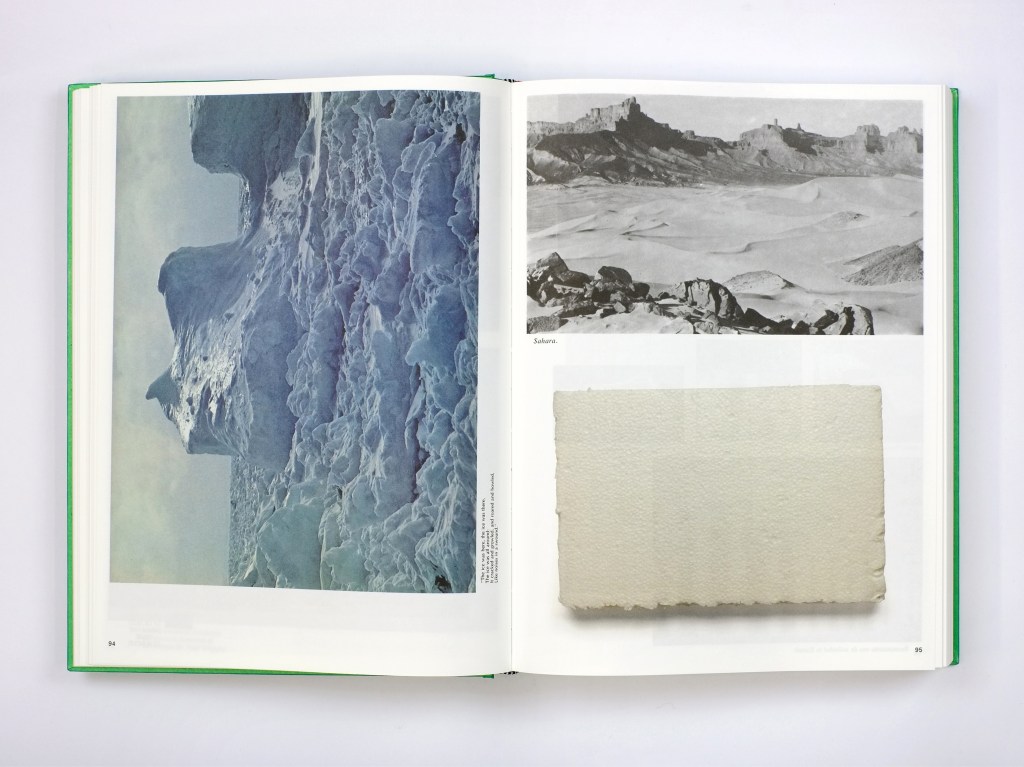

The first spread of Parallel Encyclopedia presents works by Julian Stanczak, Marina Apollonio, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Marcello Morandini, Tadasky, and Mosuho Ohno—all artists linked to the Op Art movement. These are striking geometries designed to enchant or deceive the eye. Turning the page, we find images of plankton, their microscopic marine forms arranged in geometries recalling those just seen. In the same spread, however, there is also a test chart used to calibrate a camera’s greyscale, made of circles, lines, and triangles. Forms echo one another. Later, there are photographs of planets, seashells, everyday utensils. A few pages on, enlargements of snowflakes and ancient cameos inlaid with human figures. The further you go, the more you are drawn into a narrative of visual analogies and shared meanings. Without any sense of rupture, on page 50 we are confronted with atomic explosions, American aircraft carriers, road accidents. On page 300 we see an eighteenth-century stool whose legs, in the next spread, rhyme with those of oxen pulling a plough. This opens an entire section devoted to horses: engravings, paintings by Velázquez and Simone Martini. There’s even a photograph of a tiger, with its trainer, resting calmly on the back of an elephant. Buster Keaton next to a medieval miniature. Dürer and an Assyrian sculpture. African art, X-rays, commercial catalogues. Centripetal and centrifugal force. Tintoretto and Yves Klein, Giotto and Walker Evans. A fascinating journey, a flow with no narration, yet one that holds attention like the plot of a thriller. Where will the next page lead?

After her encounter with Aby Warburg, another unexpected meeting shaped Batia Suter’s path. “My mother is a psychologist. Once, while I was talking to her in her studio, my eye fell on Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung. I picked it up and started reading.” For the artist, it was another shock: “Again, his way of thinking about images was very close to mine. He talks about ‘Urbilder’—primordial images developed by the unconscious and common to all humanity.” Jung studied dreams, fantasies, and religious symbols to show the recurrence of certain universal imaginative forms. “It’s a very powerful idea—that human beings all react the same way to certain visual information. It’s something natural. And for me, that’s very clear. I’m convinced that such a thing exists: at a primitive level, we are stimulated by certain subjects and images and by their qualities.” And yet Suter felt something was off: “I knew I didn’t want to go in a psychological or spiritual direction. I had to step back, stop, to understand better what I was looking for.” Again, the crisis became an opportunity for a fresh start, and Suter returned to immersing herself in her world of photographs, working to refine her language so that the invisible thread binding her compositions would become ever more transparent to the viewer. But in the end, what kind of language is it? “It’s similar to the language of dreams. It’s fast, associative, non-rational. I create unexpected connections between images to generate new meanings. I’m not trying to explain everything verbally, but to provoke a visual experience. A language that operates beyond words, touching something more fundamental in human experience.”

Nine years after Parallel Encyclopedia, in 2016, Suter released Parallel Encyclopedia #2. Same format, same method, same number of pages. But unlike so many film sequels, this second volume stands on its own. The artist introduces colour—sparingly. The layout is slightly more elaborate. There is perhaps more humour. But again, the flow of thousands of images manages to embrace all human knowledge, from the micro to the macro, from the ancient to the contemporary. From this volume—as from the others that followed, particularly Radial Grammar (2018)—came installations in which Suter allowed images to interact with space. They could take the form of large-scale prints, slideshows, projections. “Installations allow me to explore physical space, to walk among the images. Here, the images become almost like a ‘skin’ of the wall, interacting with the architecture.” She conceives these operations as “extractions” of one or more chapters from her books—extensions of her editorial projects. If the experience of a book is intimate and repeatable, its “spatial staging” becomes something physical, where the viewer confronts images larger than their own body, able to be examined up close or from afar. The same is happening these weeks in the dark spaces of the Roman cryptoporticus in the historic centre of Arles, where Suter has been invited to present Octahydra for the Rencontres de la Photographie. It is a projection-based work reflecting, on one side, on architectural forms, and on the other, on images of food containers whose rhythmic, architectural patterns evoke structures of defence and protection.

Suter’s is a language that eludes immediate rationality, yet is universally understandable. Like music, in a way. The images she gathers, through a kind of ancestral pull, are not mere representations but words in a discourse grasped almost unconsciously. As she herself admits, we live in a moment when—overwhelmed by a constant flow of visual stimuli—“reflection is almost impossible.” And these images she uses, drawn from the past—a past arriving to us through the printed page—appear perhaps as the last handholds to keep us from drifting away, in a context where it is ever harder to distinguish what is true from what is not.