by Luca Fiore

When her first book, Sequester, was released in 2014, The Guardian’s photography critic, Sean O’Hagan, wrote that the volume was “laden with an inordinate sense of silence. Her monochrome landscapes, made using long exposures at dusk or early morning, alert us in their meditative way not just to the thereness, but also to what James Joyce called the ‘whatness’ of things.” He continued: “One senses that, for Awoiska van der Molen, photography is like a metaphysical quest, a journey to the essence of things. Her images take me back to Nan Shepherd’s classic book, The Living Mountain, which recounts, in luminous prose, the Scottish writer’s lifelong fascination with the Cairngorms as a physical and spiritual landscape. In it, she writes of her solitary walking and looking: ‘It is a journey into Being: for as I penetrate more deeply into the mountain’s life, I penetrate also into my own. For an hour I am beyond desire… I am not out of myself, but in myself. I am. To know Being, that is the final grace accorded from the mountain.’ That grace exists, too, in these quiet photographs of a world both desolate and beautiful.”

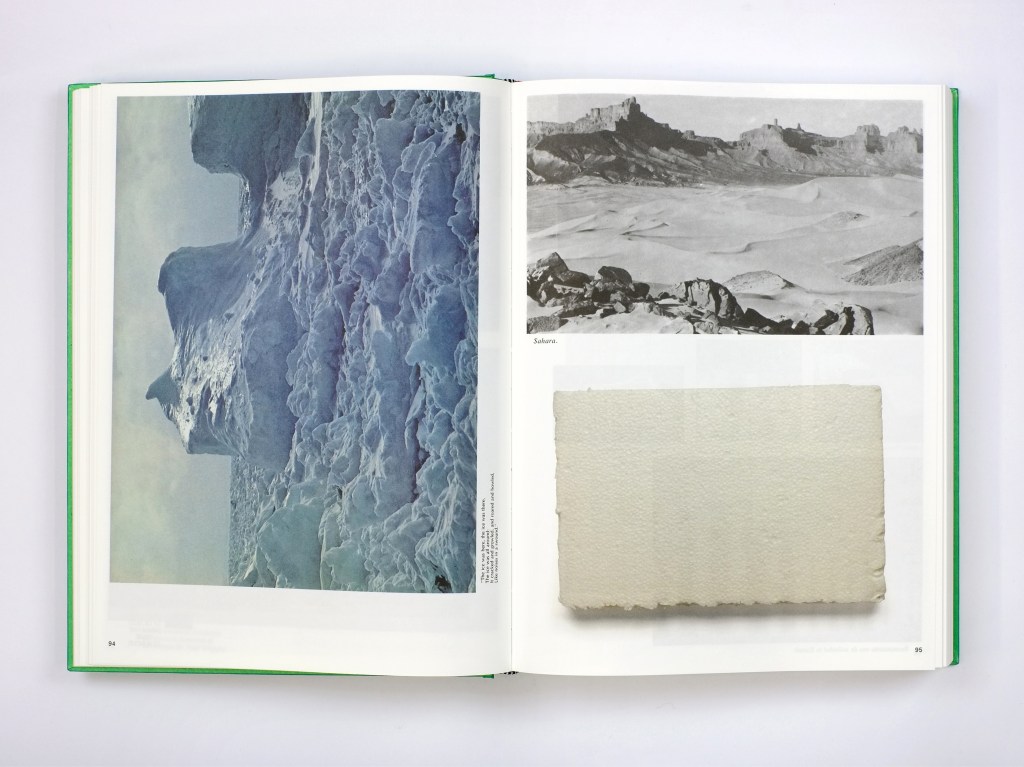

Since then, for Awoiska, born in Groningen, the Netherlands, in 1972, her career has been on a constant rise. Sequester (Fw:Books, 2014) was shortlisted for the Aperture/Paris Photo award, followed by the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize in 2017 and the Prix Pictet in 2019. In the meantime, she published three other books: Blanco (Fw:Books, 2017), The Living Mountain (Fw:Books, 2019), and The Humanness of Our Lonely Selves (Fw:Books, 2024), the latter again selected for Aperture/Paris Photo. Today, her photographs are part of the collections of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the De Young Museum in San Francisco, and the Museum of Photography in Seoul.

“I didn’t want to become an artist. I grew up in what I would call a disharmonious and chaotic family, with my mother a painter and my grandfather a sculptor. I wanted a normal life, a normal job,” she tells Il Foglio. “I started a Tourism school because I wanted to travel, but I quit after two years. I enrolled in art school, studying architecture, thinking I would find a job in an office. But even that didn’t work out.” At twenty-five, she found herself without a clear direction. While working as a waitress, she took a course in photography and darkroom printing. There, she finally realized she had found “the right thing for her” and decided to return to art school to study photography. “I had the chance to work in solitude, having control over the entire process. It was just me, the camera, the chemicals, and the things in front of me.”

During her studies, she stumbled upon a book by Wim Wenders, Written In The West, in which the German director recounted his location scouting in the United States for Paris, Texas. “I wasn’t so much struck by the American landscapes, but by an interview where Wenders explained that what he was looking for was ‘the end of the world, where everything is finally silent.’ I wondered what it would mean for me, in the Netherlands, such an urbanized place, to go in search of the same thing.” She began a series of portraits of young Dutch people living in the North, near the dikes, far from the rest of the world. Awoiska asked herself, “What are they doing there? Why aren’t they looking for anything else?” This became her graduation project. But what next? What else was there to photograph?

“There are many artists who move from one project to another with great ease. They have an idea, they realize it, and then they move on to another. But for me, it doesn’t work that way. I don’t love the term ‘project,’ which is so overused. I’ve always been more interested in understanding the inner drive, the intrinsic motivation that leads me to create images. I tend to go where things take me.” So, during her Master’s in photography in Breda, she found herself traveling by train along the northern coast of Germany, which, in her thoughts, was again a kind of “end of the world.” There, she found a group of artisans engaged in rebuilding a medieval shipwreck. “Unlike my previous subjects,” she recalls, “these men and women didn’t worry about their appearance or how they would look in photos. I noted in my journal that they seemed ‘without vanity’ and ‘uninfluenced by the outside world.’ It was a kind of epiphany that strengthened the common thread present in all my subsequent works.” So, it wasn’t about portraying people in particular situations, but about something that had that characteristic of purity or, perhaps, imperturbability. Or maybe the right term is “sprezzatura.” In fact, after that trip, she started focusing on urban landscapes, photographing them from the outside and the inside. “I was looking for the same experience I had with the German artisans: places that seemed untouched by the outside world. I realized that those buildings, especially at night, offered me support. I felt them, in some way, rooted. Something I could lean on. In the daytime tumult of the city, photographing them helped me find peace and feel more rooted myself.”

For six years, she photographed nothing else: industrial buildings, suburban street corners, anonymous interiors, old armchairs, radiators. All nocturnal images, where the absence of people suggested a sense of quiet. Then, one day, while looking back at some of these images, she noticed a patch of black earth on which one of these houses stood. It was a photograph taken a year earlier, but in that moment she thought, “That’s where I need to be.” This marked the beginning of her great landscape period, which would occupy Awoiska van der Molen for the next decade and take its first stable form in 2014 with Sequester, as we mentioned.

Of that book, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, one of the sharpest and most elegant pens in contemporary photography criticism, wrote: “The photographs describe surfaces, fissures, and rolling expanses of an unspecified landscape, taken with long exposures on nights of profound shadow, when each scene is illuminated by the light of a distant moon. What we see in each image is therefore the accumulated compression of many minutes or hours of light traveling across a dark scene, so that ravines, trees, rock faces, leaves, and slopes are lit by a light that casts no shadows in the darkness surrounding them.” He continues: “Amidst all this darkness, these images are animated by life, and by a sense of its spread into the imperceptible depths of shadow, where the silhouettes of leaves transform into spores with rough and blurred edges. Trees seem to reach for the light, while the jagged pattern of shadow and light animates the surfaces of the grass, and in the diaphanous shimmer of this nocturnal light, we feel like explorers of a deep and pristine ocean.”

Van der Molen has traveled across Europe in her Fiat Marea, stopping in safe places and sleeping in the back seat. She has been everywhere, she says, “from Spain to Crete, passing through Norway.” In her book, no location is specified, because it is not a work about places. Instead, she explains: “I only take the camera out of my bag when, in a place, I feel a connection between my ephemeral and transient self and what is eternal and solid. In these places I photograph, what I feel is a deep sense of rootedness. Photography is the result of this connection, of this experience. I’m not documenting the landscape: I’m photographing what I perceive by being in nature. The place we come from.” It’s one thing to say it, another is to create convincing images that can convey the same experience to the viewer. The artist says that after an entire year of work, there were only five or six “good” photographs. And, working with analog, you only find out if a shot was successful weeks later. It’s so easy to fall into the temptation of the rhetoric of the sublime that comes from romantic painting, she explains: “It’s like photographing a person smiling. Everyone likes a beautiful smile. But is it really the expression that says the most about us? In landscape photography, something analogous is the sky, where the eye can get lost in the depths. My attempt, however, is not to let the gaze escape.” It’s almost the search for a centripetal rather than centrifugal force. An invitation to an immersion.

Then, at a certain point, after ten years of work, Awoiska realized she was repeating herself. “I learned a lot about myself during that period, and perhaps that’s why I no longer felt the need to continue that search.” So, while in Japan looking for new landscape images, she happened to photograph, at night, the grid of orthogonal lines drawn by the windows of a traditional Japanese house. The opaque panes prevented a view of the interior but returned a soft light, discreetly illuminating the darkness of the street. Back in Amsterdam, she looked at the image and said to herself, “No, too pretty.” But the following year, she returned to Kyoto to photograph nature and made a few more images with the same kind of subject. “But in the third year, I went again knowing that I would only photograph the windows. I didn’t know yet why or what I would do with them. I just knew that was what interested me. But there are those situations where you have no idea why you’re doing something, you just do it in response to what’s happening. It’s horrible to hear, but these are moments when you feel happy.” As in one of her photographs, Awoiska’s story is made of lights emerging from the deepest blacks. If I think back to the first time I photographed a window, in 2015, I realize it was a period when I felt lonely. Over time that personal experience passed, but it made me aware of an epidemic of loneliness that was afflicting a country like Japan and, ultimately, our entire society. Thus, as had happened with the nocturnal landscape, the photographs of the windows became a kind of psychological space for the artist to explore. Those luminescent panes become a kind of separating membrane, a defensive barrier, but also a breach in a closed world. “The more time passes, the more I think that this kind of loneliness is at the root of many difficulties, not just personal ones. I think that certain political behaviors, cultural choices based on fear, ultimately grow from this feeling of isolation and lack of connection.”

It would be wrong to create a cause-and-effect connection, because it’s never like that in van der Molen’s work. But perhaps it’s no coincidence that from the mysterious images of the grid of squares/windows captured from a medium distance, the artist began to get closer to the glass, framing the objects leaning against the opaque panes. They resemble bodies pushing outwards. “I was surprised by these new images. They had a new intimate, even sensual, quality. And I asked myself what they were saying about me. Was there perhaps a desire for greater intimacy?” The book that resulted from this is titled The Humanness of Our Lonely Selves and is a unique object, bound as a leporello with the photographs of the windows and a 16-page insert with the images of the glass. A design object in itself, it sold out in just two months.

Awoiska only understands herself and her work in retrospect. Today, she thinks back to the cover of Sequester, a photo she initially discarded because it was “too pretty.” A year later, she recounts, upon re-examining the negative, she changed her mind: “It seemed like a Japanese drawing to me, with flowers at the edges and the center empty—a space that in Japan would be called ‘Ma.’ I had never used it before; I considered it ‘their’ concept, not mine. But I realized that in that image there was also the meaning of darkness in my work: a black hole on the border between heaven and hell, life and death, beginning and end.” She shares this because, with the window series, things seem to have reversed: “In the center, there is a bright white, surrounded by darkness. I don’t want to cross that white space; I prefer to stay in that darkness which for me is like a warm blanket. Even if the windows can be born from a feeling of loneliness, I don’t try to interpret too much. Yet, comparing the covers of these two books, I see an interesting, almost ironic, inversion. An unexpected reversal.”