by Luca Fiore

There is a poem by William Blake titled The Evening Star that reads:

Thou fair-haired angel of the evening,

Now, whilst the sun rests on the mountains, light

Thy bright torch of love; thy radiant crown

Put on, and smile upon our evening bed!

Smile on our loves, and while thou drawest

The blue curtains of the sky, scatter thy silver dew

On every flower that shuts its sweet eyes

In timely sleep. Let thy west wing sleep on

The lake; speak silence with thy glimmering eyes,

And wash the dusk with silver. Soon, full soon,

Dost thou withdraw; then the wolf rages wide,

And the lion glares through the dun forest.

The fleeces of our flocks are covered with

Thy sacred dew; protect them with thine influence.

These lines by the English poet open Summer Nights, Walking, perhaps the most well-known book by American photographer Robert Adams, recently republished by the German publisher Steidl, after the second edition by Aperture went out of print and became a collector’s item—and a cult object. As he often does with his books, Adams wrote a short introductory text for the image sequence. In this case, he writes:

“Since childhood we remember the beauty and peace of summer evenings and want to believe that what we saw then is timeless. That hope guided my selection of pictures for the first version of this book, Summer Nights, in 1985. More recently, however, when I looked again at the photographs I might have included but didn’t, it seemed that if I had chosen a wider variety, the result, though less harmonious, would be more convincing, closer to our actual experience of wonder, anxiety, and stillness. The prayer by William Blake that appeared at the beginning of the original edition remains, I believe, appropriate for this revised and expanded version, recognizing the splendor of Creation but also the reality of the wolf and the lion1.”

In Italy—as is often the case with great masters of photography, whether American or Italian—the name Robert Adams, born in 1937, is little known beyond a small circle of specialists. And yet many consider him the greatest living American photographer. Joshua Chuang, until recently at the helm of the Yale University Art Gallery and now Director of Photography at the global art powerhouse Gagosian, is the person who has worked most closely with the master over the past fifteen years. He tells Il Foglio:

“I don’t know if it makes sense to call him the greatest—it depends on what criteria you use—but what I can say is that I can’t think of any other American artist who has tackled the enigma of human existence and how to move through the world today with such precision.”

For Chuang, Adams’s lineage is that of Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, and John Sloan, “who portrayed life while recognizing both its beauty and its cruelty.”

To understand the intellectual trajectory of this giant of photography—who has also written some of the most profound reflections on the artistic experience as such, collected in Beauty in Photography (in Italian as La bellezza in fotografia, edited by Paolo Costantini for Bollati Boringhieri) and Along Some Rivers (Lungo i fiumi, Itaca/Ultreya, edited by Giovanni Chiaramonte)—it’s worth revisiting his biography.

Robert Adams was born 86 years ago in Orange, New Jersey, just a few dozen miles from New York City, into a devout Methodist family. In 1947, the Adams family moved to Madison, Wisconsin, and in 1952 to the outskirts of Denver, Colorado, in search of a better climate for treating young Robert’s asthma. The encounter with the landscape of the American West was initially destabilizing. “What he discovers is a very particular kind of beauty,” Chuang explains, “not the sublime sought by earlier photographers in the wilderness of national parks, but a fascination rooted in the embrace of solitude and silence.”

As a boy, Adams joined the Boy Scouts, and his nature-loving father took him hiking and rafting. “I remember how desolate [Colorado] seemed to me, coming from Wisconsin,” Adams said in a 1978 lecture in New York. “Even in spring, nothing seemed to be happening—maybe just a bit more wind. Only gradually did I learn to anticipate the arrival of doves from Mexico, the blooming of chicory… there were so many wonderful things happening.”

His first contact with photography came in 1955, when his sister Carolyn gave him the catalog of The Family of Man, the legendary exhibition curated by Edward Steichen for MoMA, which toured dozens of cities in the U.S. and Europe and also arrived at the Denver Art Museum.

Despite his interest in the visual arts, Adams enrolled in English literature, first at the University of Colorado at Boulder, then at the University of Redlands in California, where he earned his degree, and later pursued a doctorate at the University of Southern California. His time at Redlands—a university founded by American Baptist Churches—was ambivalent: it put him off pursuing a clerical career, but intellectually it was deeply stimulating. The turning point was his encounter with Professor William W. Main.

Chuang recounts: “He was a jazz pianist, always poking fun at pedantry. He quoted Nietzsche and the Bible with ease, and never minced words. He used to say: ‘Books should bite the reader.’”

During a seminar on 20th-century European literature, Adams studied A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses by James Joyce. He focused on the character of Stephen Dedalus, who in Portrait undergoes a transformation from self-indulgence, through religiosity, to the pursuit of art. However, in Ulysses, Dedalus appears as a would-be poet whose creative potential remains unfulfilled. Adams argued that Dedalus fails as an artist because he cannot reconcile his love for beauty with the conviction that God is present everywhere, even in the mundane, in a “cry in the street.”

Furthermore, Adams saw Stephen’s failure as a warning against an aestheticist drift, which “demands the worship of beauty—a trait far from universal in the human world—and thereby excludes the worship of God, the great common denominator of existence.”

Another theme that fascinated Adams, according to Chuang, was that of Sophocles’ Oedipus. “For the young Adams, the Greek tragedian portrayed humanity as both aware and ignorant, free and bound by fate, innocent and guilty. He believed contemporary European playwrights had flattened this paradox, refusing to acknowledge the contradictory nature of humanity and thus diminishing it.”

A third key influence was the Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr who, in his book The Nature and Destiny of Man, wrote:

“Christianity and Greek tragedy agree that guilt and creativity are inextricably linked. Sin indeed accompanies every creative act, though evil is not a part of creativity; it arises from the self-centeredness and selfishness with which man disrupts the harmony of being.”

Adams bought his first camera in 1963 and began photographing around Denver in his spare time, while teaching literature at Colorado College in Colorado Springs. He studied Camera Work and Aperture and learned photographic technique from documentarian Myron Wood. Three years later, he purchased a print of Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1944 by Ansel Adams.

Chuang notes: “It’s an atypical image in the canon of the Californian master of the sublime. There’s not just a majestic landscape with snow-capped mountains, but a village on the plain, a mud-brick church, and a cemetery. There’s a profound relationship between nature and human existence—not heroic, but humble and everyday.”

That relationship between landscape and human presence would remain at the core of Robert Adams’s vision—a wound never quite healed. Upon returning home from university, he remarked:

“I came back to Colorado only to find that it had become like California… The places I had worked, hunted, climbed, the rivers—all were being destroyed. My desperate question was: how can one survive this?”

Wilderness was being threatened by reckless human development, a frenzy that struck him as a whirlwind of arrogance.

But in 1968, a turning point came that would show him a possible way out of this paralysis—moral before it was creative. How to photograph a landscape besieged by human activity? Was innocence lost forever?

The occasion was a trip to Europe, visiting his wife Kristin’s family in Sweden. In Germany, Adams visited several churches designed by architect Rudolf Schwarz, a friend of theologian Romano Guardini. One church, St. Christophorus in Cologne, stood out. He would later say it showed how a simple, austere space could “contain the uncontainable.”

According to Chuang, Adams found in Schwarz’s architecture a viable model for reconciling the longing for beauty with the contradictory nature of human experience. These were buildings born, in some sense, out of the tragedy of WWII bombings, and yet they managed to convey peace.

“Back home,” Chuang says, “he resolved to follow that path: each of his frames would become a container for the uncontainable. His photographs are like haiku, where every detail is necessary. Form and content coincide. That’s what sets him apart from contemporaries like William Eggleston or Stephen Shore, where style often overtakes content, rendering it almost irrelevant.”

According to Giovanni Chiaramonte, Adams’s photography “reveals a vision based on formal analysis, poetically close to Paul Cézanne, and far removed from rhetorical flourish in composition or print tonality. He favors the quiet clarity of midtones over the dramatic contrast of whites and deep blacks characteristic of earlier masters like Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, or Minor White.”

John Szarkowski, legendary MoMA photography curator who gave Adams a major show in 1979, wrote:

“His pictures are so civil, balanced, and rigorous—so averse to hyperbole, theatrical gesture, moral imposition, and expressive effect—that some viewers might find them dull… Others, for whom the noisy excesses of conventional rhetoric have lost their power, may find in these images enrichment, surprise, instruction, clarification, stimulus—and perhaps hope.”

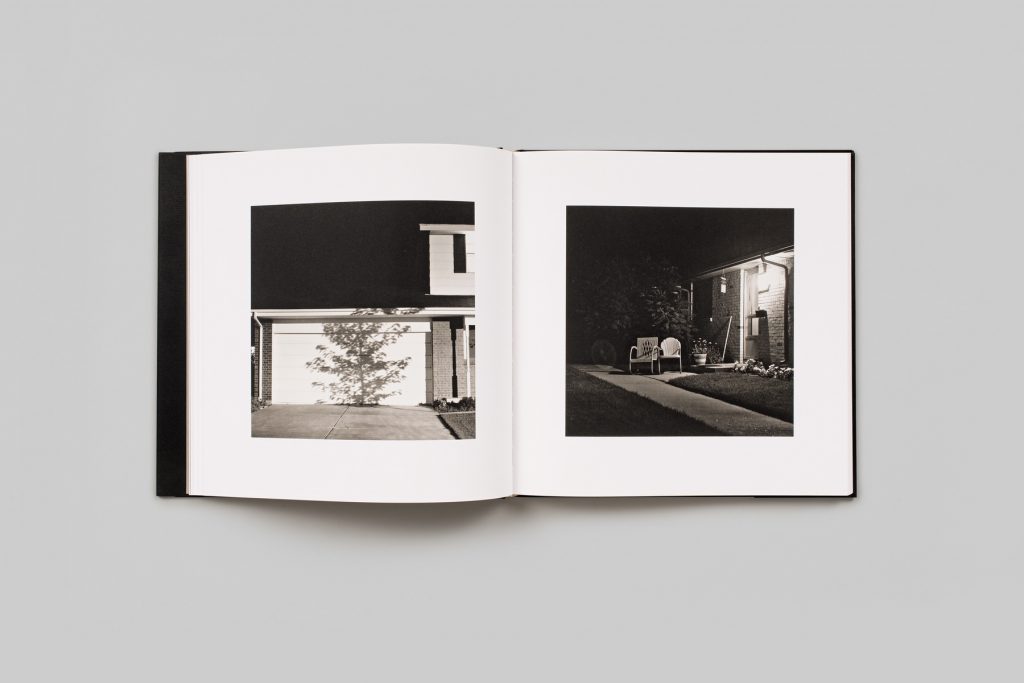

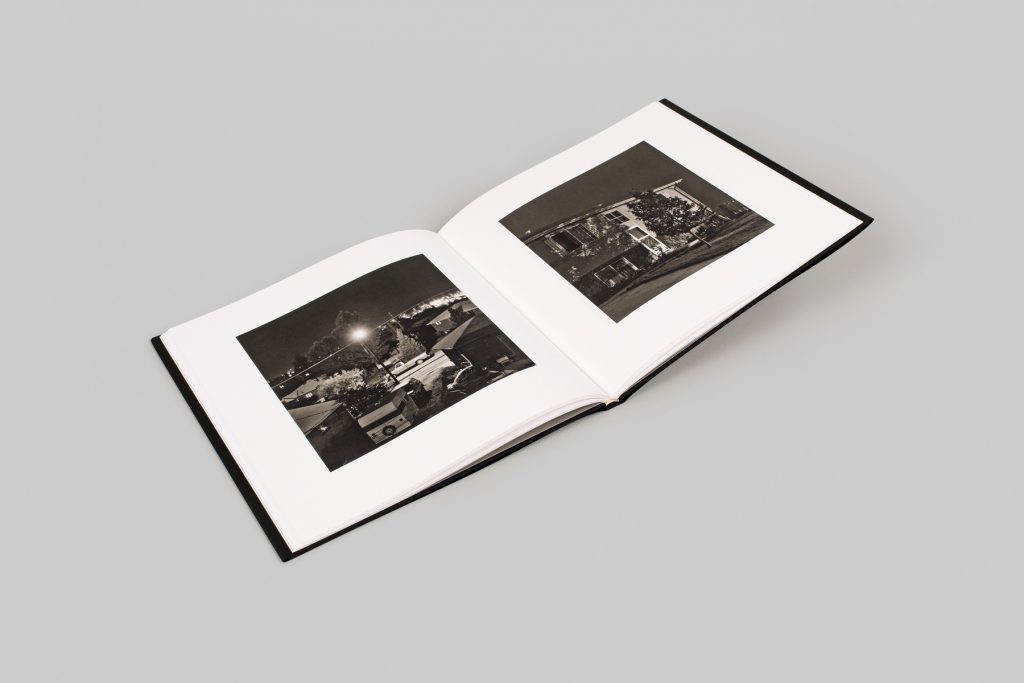

Summer Nights, Walking is perhaps the fullest expression of this vision. Made between 1976 and 1982 around his home in Longmont, Colorado, the book shows nighttime scenes of empty streets, country paths, woodland edges. Clouds still lit by the sun over a landscape already in darkness. Tree shadows cast on white suburban homes. A carousel, like a spaceship ready to launch.

He shows us what most of us take for granted but rarely notice: the few zones of the world visible at night are outlined by a combination of lingering sunlight (often reflected moonlight) and artificial lighting (streetlamps, shop signs, car headlights). Photography is perfectly capable of rendering these odd conditions—but until Adams, no one had bothered to do it with such finesse.

Luigi Ghirri once wrote:

“Adams searches more in the light than in the landscape for the narrative thread; and the nighttime sequence is more a study of light than a view of the world at night. His Summer Nights series seems to recall the darkness toward which we are headed, an end-of-the-century atmosphere accentuated by his black-and-white tonality—a poetic attempt to still see something.”

Ultimately, if light itself is the true subject of all of Adams’s photography, it’s a point he makes in his most famous essay, Beauty in Photography:

“William Carlos Williams said that poets write for a single reason—to give witness to splendor (a word used also by Thomas Aquinas to define beauty). It’s a good word for photographers, because it relates to light: a light of inescapable intensity. The form that art seeks is of such radiance that we cannot look at it directly. We are therefore forced to glimpse it in the broken light it casts on our ordinary objects. Art can never fully define the light.”

In recent years, Adams—now retired and nearly silent, like a photographic Cormac McCarthy—has become a point of reference for many younger photographers who write to him seeking advice or feedback.

As long as his eyesight allowed, he replied by hand, via regular mail. One such photographer is Gregory Halpern, now a leading voice in American photography, who sent Adams the draft of Zzyzx (later a major success). He received this reply:

“Beauty, and its implication of promise, is the metaphor that gives art its value. It helps us discover some of our better intuitions—those that encourage care.”

Robert Adams’s images, with their mute eloquence, come from a deeply unsettled mind—capable of outrage (especially aesthetic, but not only) and of profound emotion at the sight of, say, a power line lit by moonlight.

His is an intelligent sensitivity that has never accepted reducing what we see to only what is visible. When asked by William McEwan what he was trying to accomplish in his life as a photographer, Adams replied:

“To learn not to complain, I think. Robert Frost once said that the best accomplishment in life is learning to be kind—something I feel very close to, and very difficult. I’m like a woman who takes her child to the beach and watches a wave carry him off. She promises God that if the child is returned, she’ll never ask for anything again. The next wave brings him back safely. She runs to embrace him, then realizes the child has lost his hat. ‘The hat, Lord,’ she asks. ‘What happened to the hat?’”

Note: 1: This is a translation produced using AI, and the quotations are not literal, but translations from the Italian translation.